I normally try to not let politics mingle with my photography, mostly because I’m not that political of a person. However, last week’s shootings in California hit a little too close to home, and today I’m feeling the weight of it all.

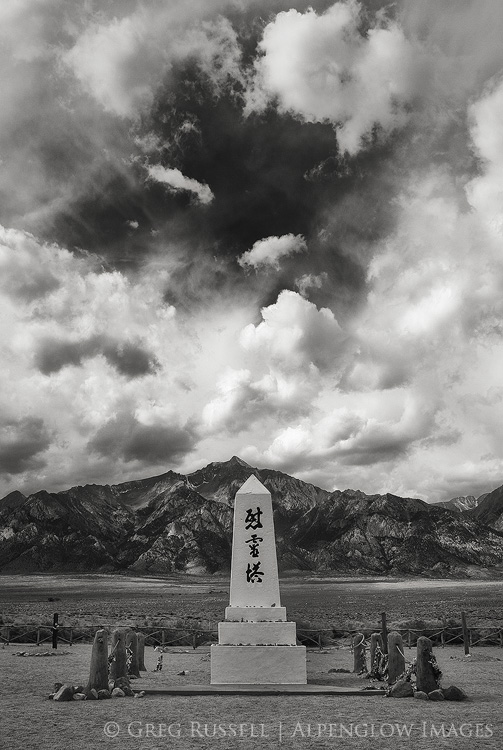

Today, I’m thinking about this image, which I made back in 2010 in the cemetery at Manzanar National Historic Site. If you’ve spent any time in the eastern Sierra, you’ve surely driven by, maybe even stopped. Manzanar was one of the internment camps that the U.S. government established after the bombing of Pearl Harbor to house Japanese-American citizens. These internment camps were the result of the mass hysteria of not knowing who the enemy might be as the U.S. entered World War II.

Upon reflection, our view of Japanese-Americans was painted with the broad brushstrokes of fear–an entire ethnic group was characterized based on the actions of a government across the Pacific.

It’s been a rough month, with the Paris bombings, various attacks elsewhere, capped off by the largest mass shooting seen in the U.S. in two years. Of course no reasonable person wants to see these things happen, but at the same time, we struggle for someone to “blame”–perhaps knowing we can pin the blame on someone, or something, helps ease the sting a little bit, helps us make sense of it.

In making peace with these senseless deaths, history seems to be repeating itself, and many people are once again painting an entire religion with broad brushstrokes, based on the actions of a few. The growing hysteria and now-cyclical rhetoric is no doubt fueled by ongoing debates between presidential candidates, social media, and the conflation of this discussion with that of gun control.

I’ve only stopped at Manzanar once–it’s all I could handle. While the visitor center presents the role of internment camps in our history as best it can, there’s a certain melancholy that seems to have transcended the buildings and gardens, which are now gone. There’s the memory of good people being ripped from their homes and sent to places they didn’t want to go, simply because of their ethnicity. This was a low point in our country’s history; although it can’t be undone, it should be cause for serious self-reflection. The violence we face today is not a Muslim problem, a Christian problem, or an atheist problem. It’s a problem of angry people doing awful things. Stopping those awful things from happening is the topic of another blog post, which I’m not qualified to write. However, if we are to move forward as a country and search out solutions, we can’t do it divided, scared of one another, labeling one another–it simply won’t work.

Okay, now that that’s off my chest, the year is wrapping up and I’m thinking about my “best of” blog post. I’ve had a varied, but productive year, and look forward to sharing some of those images soon. Thanks for reading.