One of the most noteworthy things about being a parent, for me, has been watching my son discover the world. Now five years old, he began as basically a blank slate (although that isn’t entirely the case), and now is an incredibly independent and strong-willed little person. Like all of us, his personality and his perception of reality is shaped by the world around him. He has adopted little idiosyncrasies from both my wife and I, as well as his teachers and friends at school and other people in his life. The way these pieces have combined make him uniquely…well, unique.

That makes him special. Since we all went through something similar, this same principle makes us all special and unique. When we talk about originality in art, it’s important to remember that the same processes are at play. Every artist, regardless of the medium, draws inspiration from various sources, and their art is simply the result of the way in which these sources have combined to spit out something “original.” I think the distinctiveness of someone’s art is probably a product of many factors, such as how courageous they are to seek inspiration in unlikely places, their experience, the amount of introspection they’ve done to clarify their own vision, etc.

On a recent backpacking trip, I was working my way up a mountain pass that overlooked an alpine tarn. The blue-green water was shimmering as if it were full of diamonds, the blocky granite surrounding the small lake contrasted that delicacy well, and the sky had perfect puffy white clouds. What a great scene.

I highlighted the words “blocky granite” in the paragraph above because that’s the aspect of the scene that stood out to me immediately. I wanted an image of this scene, but how to portray it, such that the granite blocks–almost like cord wood–would be accentuated? Immediately I thought of the woodblock prints of Chiura Obata, a Japanese-American artist who produced moving paintings of the Sierra Nevada, among other places, in the first part of the last century.

I’ve always had a particular affinity for Obata’s work in the Sierra (three of his pieces–postcards–hang above my desk right now) for many reasons, not the least of which is the incredible sense of place he felt there. You can see it simply by looking at his work. When Obata, like many other Japanese-Americans, was sent to internment camps during World War II, he made art there, and you can even feel the sense of place in that work. It’s a rare quality, but his work has it.

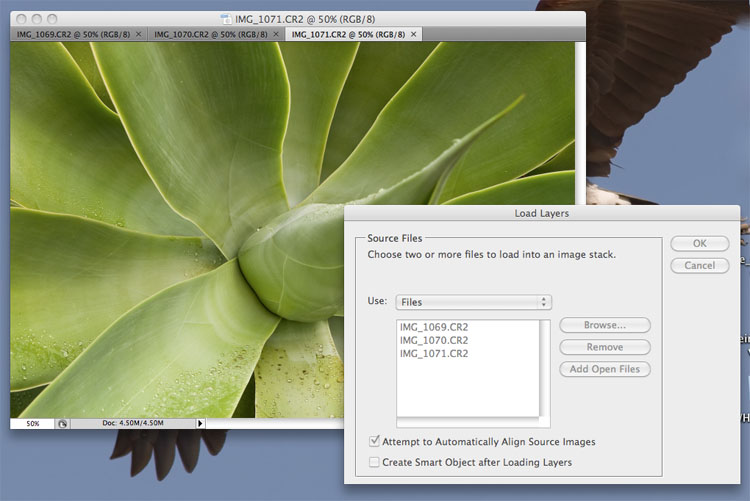

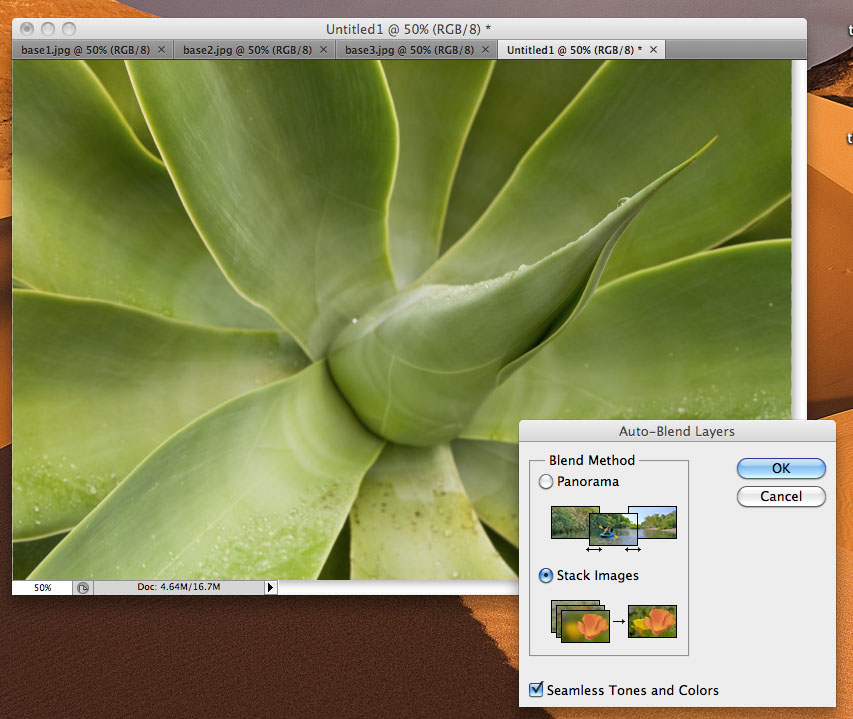

Looking at this alpine tarn, I was inspired by Obata, made some images, and when I got home I did something radical: I attempted to manipulate the image so that it would resemble a woodblock print.

The effect is a bit difficult to see on the computer screen (I imagine this would need to be appreciated as a print), but here is a 100% of the above image to see the result:

As I said above, I suspect this would make a nice print, but is difficult to appreciate here. I don’t see myself making these sorts of images with any regularity, but I thought it was important to note my thought process in making this image, because it’s good for every artist to remember that inspiration can come from the most unlikely of places, and to remain open to that. Additionally, it was an instructive exercise for me, because I got to dive back into Obata’s work, which always makes me very happy.

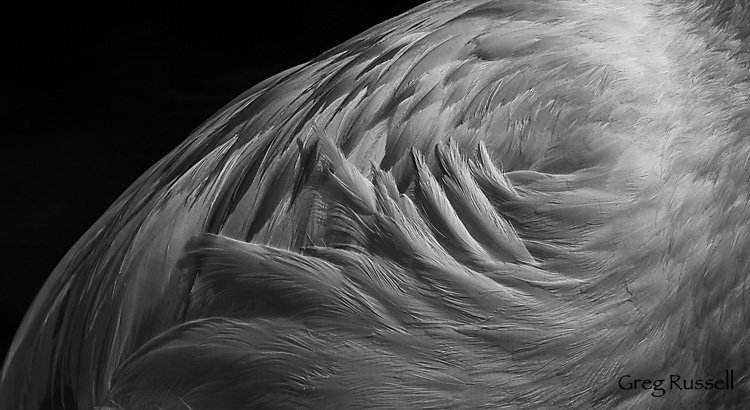

Towers of the Virgin, Zion National Park, Utah, June 2009

Towers of the Virgin, Zion National Park, Utah, June 2009