“And here we are,” said Dr. Ford.

The boy replied, “Nowhere Land.”

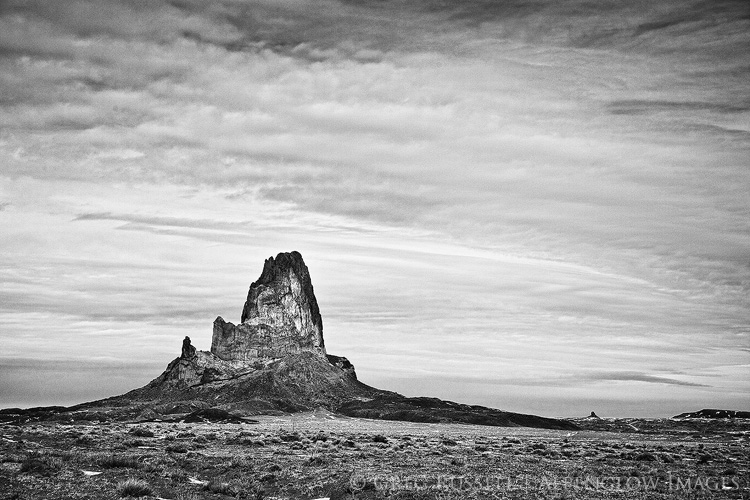

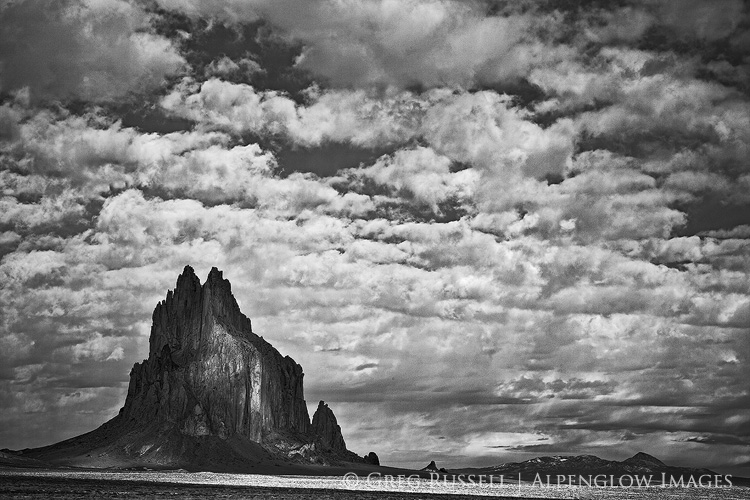

“That seems hardly a fitting name for a place so full. Can’t you see it? Perhaps you’re not looking hard enough.”

– HBO’s Westworld

It’s been over 15 years since I moved to southern California, and the sheer scale & emptiness of its massive deserts are still coming into perspective. The Mojave Desert alone sprawls over 7 counties, covering 28% of California’s landmass; to truly get to know this place would take a lifetime of exploration.

To many, California’s deserts range from something that has to be tolerated on the drive from Los Angeles to Vegas to simply “the ugliest landscape I’ve ever seen.” Although many people love and cherish this landscape, it lacks intrinsic value to others. Despite (or because of?) the lack of intrinsic value, the desert is often seen as a place with only extrinsic monetary value. Because of this, it is under threat from several different directions. What are those threats, and why should we value the desert?

Solar development

If California has an abundance of anything, it’s sunshine. It shouldn’t be surprising, then, that the Mojave Desert has been identified more than once for large-scale solar development. Most solar development involves “scraping” the desert floor of its native vegetation to install large arrays of solar arrays. Depending on the type of solar development, the arrays are either solar panels, or large mirrors which direct focused sunlight upwards towards a series of solar panels at the top of a tall tower.

In an effort to curtail chaotic and unplanned solar development in the California desert, the Obama administration passed the Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan (DRECP) in 2016. The idea behind the DRECP is simple: allow renewable energy development in certain areas of California’s deserts, while permanently protecting others.

Much of the focus of the DRECP was on prime habitat for some of the southwest’s most sensitive species, including desert tortoises. For instance, the massive Chuckwalla Bench (read more about the Chuckwalla Bench and Little Chuckwalla Mountains here), which extends from eastern Joshua Tree to the Colorado River in eastern Riverside County, is one of the best and most continuous desert tortoise habitats in the state.

At the beginning of February, the Trump Administration announced plans to revisit the DRECP with the intent of rolling back some of its original protections in order to open more of California’s deserts to renewable energy development. So far they have not offered a good reason for this.

It has been questioned whether large-scale solar development really benefits the environment or not. What’s more, the Mojave Desert’s plants have been shown to be an incredibly good carbon sink, although their ability to reduce atmospheric carbon is heavily dependent on the occurrence of a wet winter. Thus, “scraping” away the plants on a large scale, or even covering them up, prevents the plants here from doing what they are best at. In solar arrays that focus light upward using mirrors, thousands of birds each year are accidentally incinerated (the Ivanpah solar array near the California-Nevada state line on Interstate 15 kills an estimated 6,000 birds/year).

Many solar projects have taken 3-4 years to build. From 2005-2016, all of the large-scale solar projects in California generated 1,470MW (megawatts) of energy. In 2015 alone, rooftop solar generated 1,050MW in California (source: Basin & Range Watch). I have said for years that rooftop solar should be mandatory on all new builds in the Southwest. Also, it is worth looking at other places for solar arrays, such as fields that are no longer farmed (as the city of Lancaster, California did). The bottom line is that there are alternatives to large-scale scrapes of critical desert habitat for solar.

Mining

As part of the DRECP rollback, the BLM has cancelled its withdrawal of conservation lands from mining claims. In other words, conservation areas that were previously protected from new mining claims now are not. The logic is that there is such little mining occurring in the Mojave Desert that any new claims would be practically imperceptible. However, that may not be the case.

Last week, two mining companies signed MOUs (Memoranda of Understanding) expressing lithium mining interests in the Mojave Desert. Standard Lithium is exploring possible lithium deposits in the area of Bristol Dry Lake, in Cadiz Valley and Pacific Imperial Mines is developing a lithium mining operation near Death Valley Junction. With the increased demand for batteries, lithium mines are becoming more and more common in the Mojave and Great Basin Deserts.

In both mining operations–and in most in the West–lithium is extracted from brine via the use of massive evaporation ponds. As water evaporates, the minerals can be extracted. It’s no wonder why these mines would be so common in this part of the world, given high mineral content of dry lake valleys.

According to Basin & Range Watch, new claims are still subject to environmental assessment. Disturbance caps (limits on the mining in a particular region) are still enforceable, but the withdrawal of these lands from the conservation plan certainly opens up the possibility that those caps could be changed in a revised DRECP.

Water

I discussed the threat of water extraction in the Cadiz Valley previously (see this blog post). It is ironic that much of the water extracted from the Cadiz Valley would likely be used in lithium mining operations, and would never actually make it to the Colorado River aqueduct.

Finding intrinsic value in a barren landscape

The science behind the desert’s importance in combating global climate change is relatively easy. Describing why the desert is beautiful to a “nonbeliever” is slightly more difficult. For me, watching a monsoon storm gather over an already imposing desert mountain range is one of the prettiest things I’ve ever seen. I also think about the first time I showed my parents a desert tortoise. Even my mom, who I wouldn’t call a desert lover, was enthralled. This past weekend, I saw my first desert pupfish in Death Valley National Park and felt a familiar and fleeting sense of joy. My son saw his first rattlesnake on a hike with me in Joshua Tree. He didn’t stop running for a solid half mile once he realized what he had just walked by, but he hasn’t forgotten about it either.

The point is that there are a million reasons to value and make memories in the desert. I can’t tell you what to value, just as I can’t tell you who to fall in love with. But, I can say that familiarity breeds intimacy, and California’s deserts need as many allies as possible right now.

While you’re developing your own relationship with the desert, there are some things you can do right now:

- Sign the online petition telling the BLM you would like to keep the DRECP intact. The BLM is accepting comments until March 22.

- Attend a public meeting to tell BLM representatives in person to keep the DRECP intact. I’ll be at the March 7 meeting in Palm Desert.

- Call or email your county supervisor. Because counties have a big role in developing the DRECP, your county supervisor will want to receive input from both residents and visitors.

California’s deserts may be barren, but they’re far from empty.