In Medicine Bow, Wyoming, they say the wind doesn’t blow twenty four hours out of the whole year. Even in July, the wind is cold, noisy, all-consuming. One morning, my friend, hiking in the wind near Medicine Bow tripped, and at the last second looked down to see a small prairie rattlesnake strike right between her legs; if she hadn’t stumbled, she would have been bitten. The wind silenced the snake’s warning rattle.

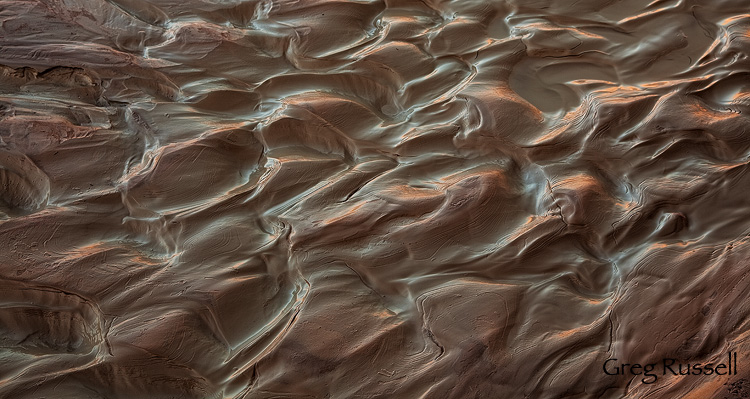

The wind can be harsh, cold, brutal, and at the same time it can be life-giving, sustaining. It shapes who we are, and what we have yet to become. If you’ve lived with it for any period of time, you know what I’m talking about. It may be much more tangible to see how the wind shapes the landscapes we love so much. I’m excited to present four new images (See the portfolio here, as well as below) from two of our national parks–Bryce Canyon and Death Valley–that are devoted to the wind that shapes these beautiful, mysterious, and awe-inspiring places.

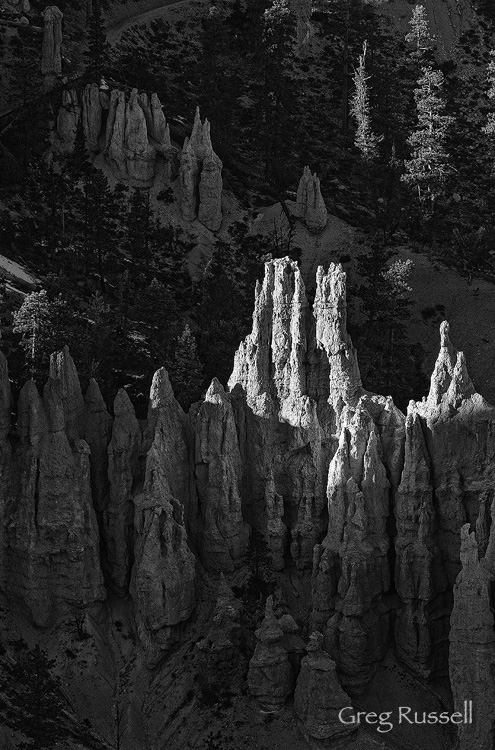

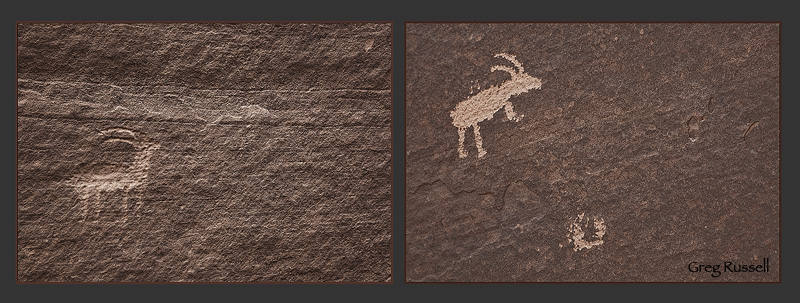

Bryce Canyon National Park is hugely popular, being part of the “Grand Circle” of the Southwest, and its no wonder why. Bryce’s hoodoos–formed by the brilliantly colorful Claron Formation–simply glow like no other rock in southern Utah. In concert with water, the wind shapes the hoodoos into various shapes–from hammers, to broken palaces, to entire cities. Jagged and raw, Bryce inspires imagination and creativity, and as Ebenezer Bryce pointed out, “its a hell of a place to lose a cow.”

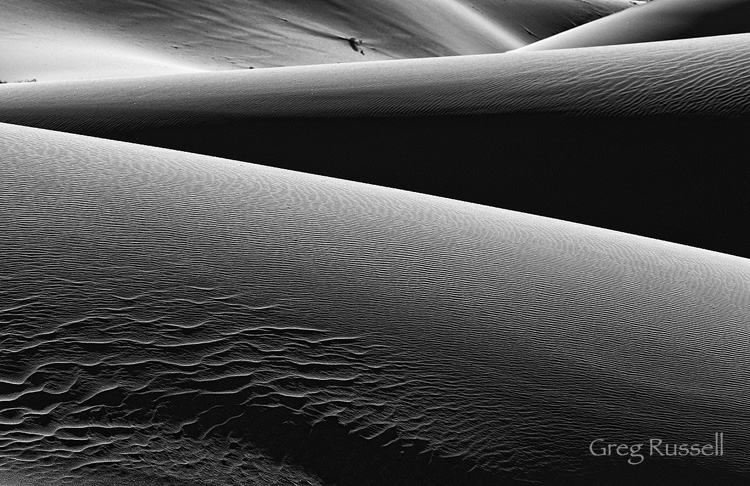

Contrast Bryce’s ruggedness with Death Valley’s seemingly endless sand dunes. The wind shapes the sand into sensuous, almost erotic, curves that perhaps could be an abstract nude study rather than a grand landscape. The light plays on the dunes on both a micro and macro scale, providing endless shapes and forms.

These images signify–in part–the forces that have shaped our national parks. To help with the continued protection of our public lands, I’ll be donating 25% of the profits from the sale of these prints to the Wilderness Society, which works to make visits to our national parks more meaningful and inspiring. This is not a limited-edition series of prints, and this offer doesn’t expire–I’ll make the donations forever. Finally, I am offering special pricing for the purchase of all four of these prints, in any size. Please visit my purchase page, or contact me for more details.

“The truest art I would strive for in any work would be to give the page the same qualities as earth: weather would land on it harshly, light would elucidate the most difficult truths; wind would sweep away obtuse padding. Finally, the lessons of impermanence taught me this: loss constitutes an odd kind of fullness; despair empties out into an unquenchable appetite for life.” –Gretel Ehrlich