In my last blog post, I talked about my opinion regarding “rules” in photography. In short, I believe it is okay to manipulate exposure or crop (for example) in order to take an image from visualization to the final product. In this post, I would like to revisit the image I introduced last time and dissect it a bit.

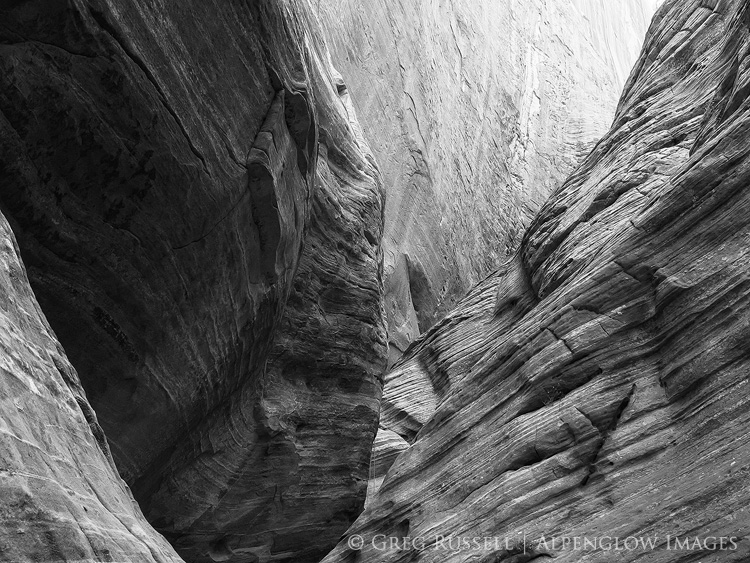

Sandstone & Clouds, March 2012

In the field

I am not normally a “grand landscape” sort of photographer; I tend to focus more on intimate scenes. However, when I saw these cliffs, what initially struck me was the fact that the buttresses were receding away from me. Although the mid-morning light had eliminated some of the shadows, I liked that each buttress was casting a bit of a shadow on the buttress behind it. This alternation of light and dark creates a wonderful sense of depth in images, and was a compositional element I wanted to take advantage of here.

Another confession: guys like me do not normally score skies like this. Cloudless blue skies are the story of my life. However, on this particular day, I was loving these high clouds; they were constantly changing and they added a great geometric element to the scene.

For me, the decision of how to balance the composition was pretty easy, and despite the fact I like to think of myself as a rebel, I roughly divided the composition into thirds. I wanted the sky to be the star of the show, so I gave it 2/3 of the frame, and I let the cliffs occupy the remainder. I like sagebrush, and wanted to leave some foreground in as well; this also gives a good visual “root” for the cliffs to sit on.

To expose the frame, I had a couple of choices. To underexpose would have meant preserving the shadows that attracted me to the scene. But, it would also introduce shadows to the foreground, which I did not really want to do. The alternative I had was to overexpose to the point where the shadows were not as dark while maintaining detail in the rest of the frame. You have probably heard the phrase, “expose to the right;” that is what I chose to do here. Phil Colla has a concise and clear explanation of the technique here.

You can always darken a scene in post-processing, but to lighten it up risks introducing noise.

To get the exposure I wanted for the lower part of the image, I had trouble preserving detail in the bright white clouds, so I made two exposures, 1 stop apart from each other.

At home

I opened the RAW files together, and in Adobe Camera RAW I adjusted the images based on the vision I had in the field. After opening the images in Photoshop, I continued this process. First I blended the images using a technique I learned several years ago from Younes Bounhar. You can read about it here. After checking carefully to make sure the images had aligned properly and there were no artifacts, I made my initial adjustments largely using Nik’s software plug-ins. The two I used here were the ‘Tonal Contrast’ filter (in Color Efex Pro), and then I used Silver Efex Pro to get the black and white conversion I wanted.

I do not have a lot to offer in terms of strategic choice on this (I did what looked best to my eye), but I only made subtle adjustments and I made careful choices based on my vision. In choosing the black and white filter, I made sure to keep the detail in the clouds, but also to make them stand out. I also kept an eye on the tonal contrast between the sagebrush and the beginning of the cliffs.

I applied a global curves layer, and then used separate levels to mask the cliffs, and selectively darken the shadows. I saved the TIFF file (with all of the layers), and then flattened, sharpened, and saved a JPEG for the web.

The beauty of image processing is that there is definitely more than one way to skin the proverbial cat. When you start with a creative vision, you learn ways to arrive at the final product in post-processing. As you gain experience, you build skills that will eventually become a tool kit that you can selectively choose from when you process more challenging images.