“We simply need that wild country available to us, even if we never do more than drive to its edge and look in. For it can be a means of reassuring ourselves of our sanity as creatures, a part of the geography of hope.” – Wallace Stegner

One year ago, our lives were changed forever when the COVID-19 pandemic made heavy landfall in the United States. As quarantine started, businesses closed, work and school went virtual, and toilet paper disappeared from store shelves (I still can’t figure that one out).

One year later, we are still working from home, and our now-feral kids are slowly beginning their release back into the wild. My wife and I have both been vaccinated fully against COVID-19, and we talk often about what the “new normal,” as it were, may look like.

The New Normal

The phrase, “the new normal,” often implies the negative and hints at things we will have to give up moving forward. Personally, I hope it’s a force for things that are more positive. For instance, I’ve really enjoyed Zoom happy hours with friends who I may not otherwise think to connect with.

If the past year has been filled with anything, it’s been a wide range of emotions. I always been too busy to be bored during quarantine. I’ve felt overwhelmed, sad, angry, as well as extraordinary happiness and contentment. There’s been a wonderful joy I’ve felt in the little things. If nothing else, the pandemic has reminded me how to feel authentic emotion. I hope that remains a part of the new normal.

The outdoors as an outlet

Raw emotion can be very overwhelming; finding a way to deal with it is key. For me that often means being outdoors; this appeared to not be unique as parks and local trails were packed with people in the early days of the pandemic. Yet, early in quarantine lockdown, many national or state parks closed. Other wilderness areas also either banned entry or asked people to stay away. The rationale was clear: a backcountry injury puts undue stress on rural healthcare systems and is not worth the risk.

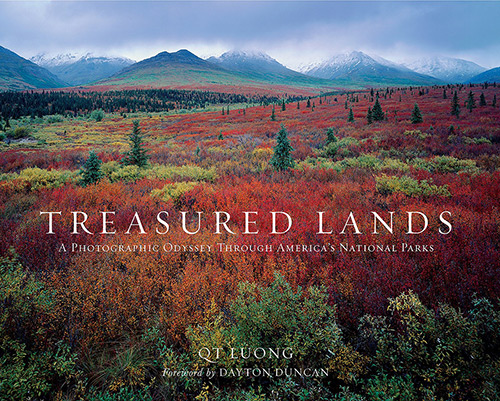

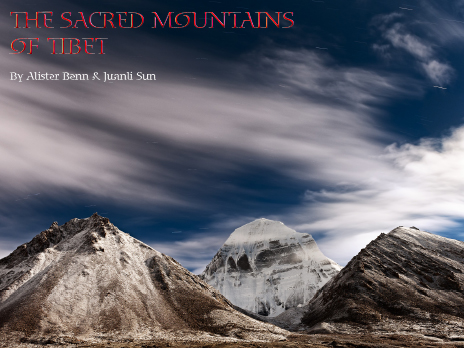

My personal escape was to resurrect images from previous wilderness trips, either processing with new skills, or using them to express my emotions in the moment. This proved to be an enjoyable and happy way to take a virtual drive to the edge of wilderness, as Wallace Stegner wrote about. This blog post has several images from previous years that I’ve processed during my time in quarantine.

As restriction started to and continue to ease, I’ve certainly enjoyed being out in the wilderness again. I’ve spent some very enjoyable days in the field working on my Wilderness Project (see posts here and here). It’s always better to be outdoors than to dream about it.

Whatever the “new normal” ends up looking like, I hope that we can remember to choose kindness, and find solace in wild places, regardless of how we visit. How have you handled the last year? How are you doing?