**Update: the public comment period has been extended an additional 120 days to September 25, 2020. This will give those with limited internet access due to COVID-19 time to comment. Still, submit your comments as soon as possible!

Driving north from Albuquerque towards Bloomfield, New Mexico through badlands and sagebrush, you pass an unassuming turnoff towards Chaco Canyon National Historic Park–a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Much of the traffic on this highway is already northern New Mexico locals, so it probably doesn’t get much attention. Tourists who do find themselves along this highway are probably more concerned with getting to mountain destinations like Durango and Pagosa Springs than stopping at what must surely be, “another point of interest.”

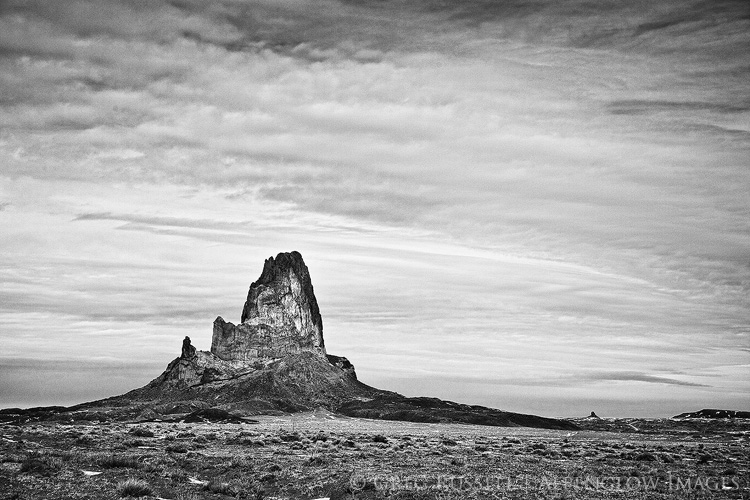

Chaco gets relatively little visitation–only 47,000 people in 2019–289th among all national park units. This little valley along the Chaco River–a tributary of the San Juan–has no immediate visual reason to draw much attention. However, from roughly 850-1250 AD, it was a cultural epicenter of the Southwest. Thousands of people lived here, traveled through here, traded here. The ruins that remain–and are protected by the Park–are some of the most extensive and well magnificent in the Southwest.

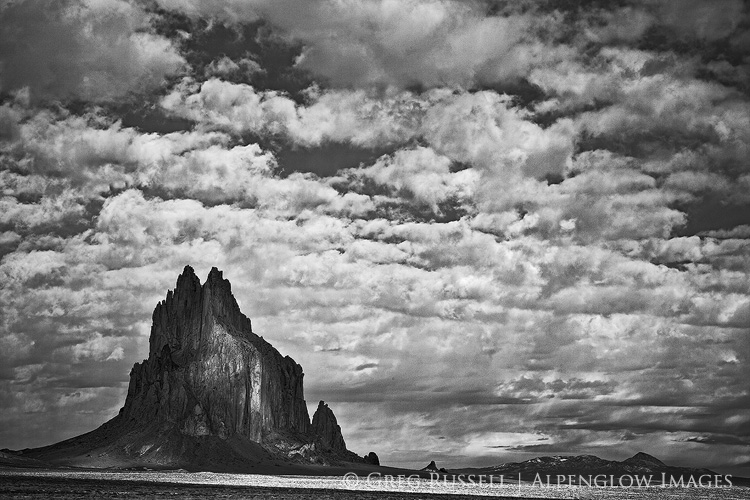

One trade route leaving Chaco–the Great North Road–runs north towards the San Juan River in an arrow-straight path. While the ruins at Chaco are full of history, the author Craig Childs walked the Great North Road and described it as being full of lithic scatter–arrowheads, pottery shards, and the like. The cultural and historic impact of Chacoan culture reaches for hundreds of miles, like ripples across the Four Corners.

Previously, a 10-mile buffer zone had been established around Chaco Canyon, withdrawing federal lands from oil and gas leases. This would preserve the integrity of Chaco from both cultural and ecological points of view. However, in early 2020, the Navajo Nation Council pulled their support for the legislation creating the buffer, citing concerns of landowner mineral rights. Local landowners complained about not having a voice with lawmakers, or not being able to have questions answered.

To that end, the BLM and Bureau of Indian Affairs has drafted a new proposal for management of the Greater Chaco landscape, with multiple options. None of the options yet takes into account the voices or concerns of local landowners, nor has the BLM agreed to delay the closing of public comments (May 28) due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Many of the most affected stakeholders do not have internet available to comment on the draft management plan.

What’s more, the Department of the Interior has commissioned two distinct ethnographic cultural studies focused on Native American ancestral ties and connections to the Greater Chaco Landscape. The results of these studies will allow for vastly improved decision-making regarding cultural use of the planning area. Pushing ahead with this management plan without the results of those studies is not the way to make decisions that will last for 20+ years.

Friends, time is short on this one. Archaeology Southwest has put together a site that will collect public comments, or you can submit your own here. Archaeology Southwest doesn’t see any of these options as viable, but recommends supporting option B1.

Thank you in advance for your support of public land!