Recently, the proliferative and educational photographers Darwin Wiggett and Samantha Chrysanthou unveiled their newest project, the League of Landscape Photographers. The intent was to be a voice of reason in a landscape photography culture that has become focused on “getting the shot,” or winning likes or shares on social media. I rather like the idea of bringing attention back to thoughtful photography and photographic projects; a huge amount of intentional but less “wow-worthy” photography seems get buried (and sadly, unseen) in the static of social media. I agree with Samantha and Darwin, who believe the first step away from this mentality begins with a tangible and published code of ethics.

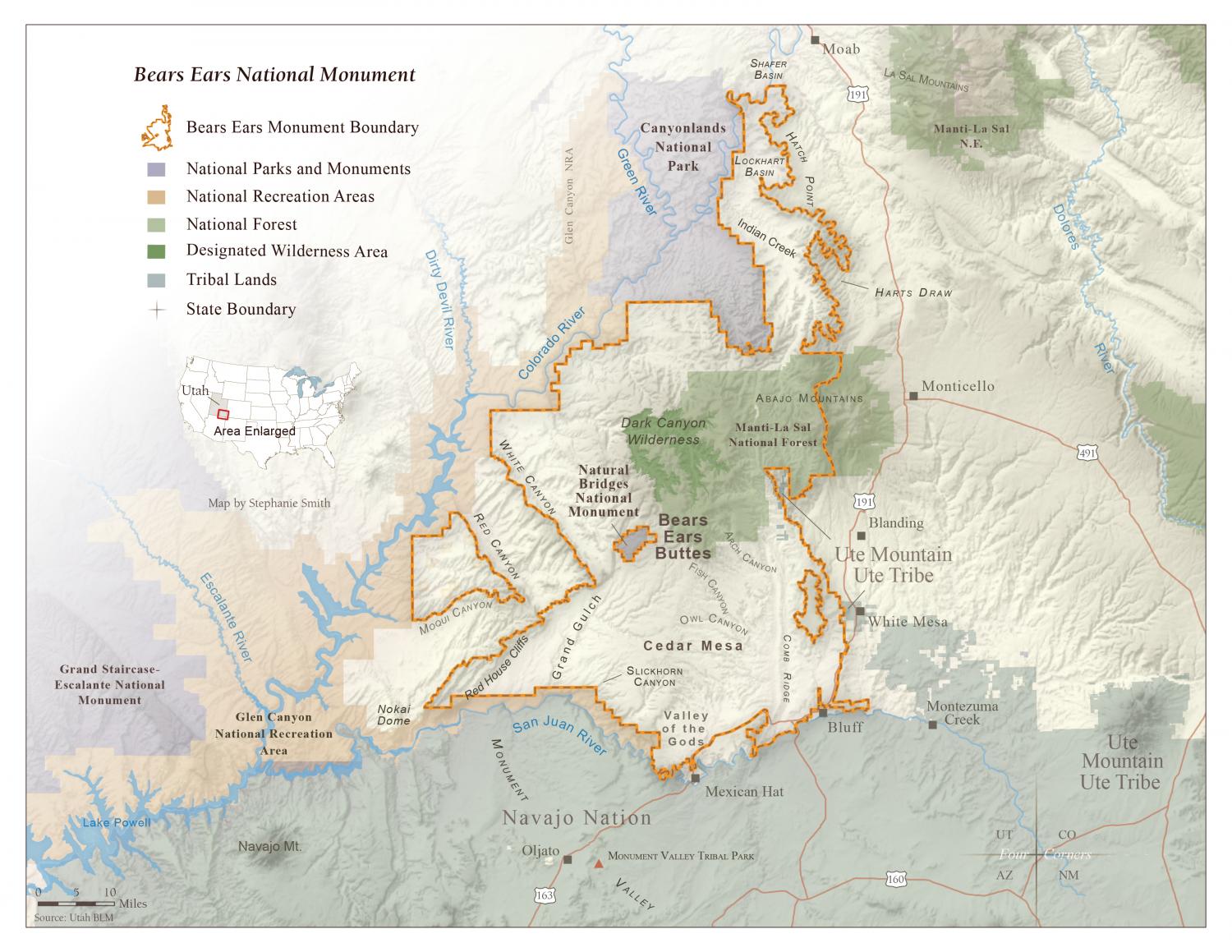

The League offers a template code of ethics here. It includes much of the stuff that you would expect landscape photographers to already be doing. Indeed, this is a comprehensive and thoughtful list. Since reading it, I’ve been thinking about something more, something I can only think to call “deep ethics.” While I’m sure anyone reading this blog, regardless of their political leanings, can say a lot about the current political climate in the United States, one thing we probably can’t argue about is that we are all paying attention, and everything we do right now matters. It turns out this dovetails well with what I consider to be my deep ethics.

“A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.” – Aldo Leopold

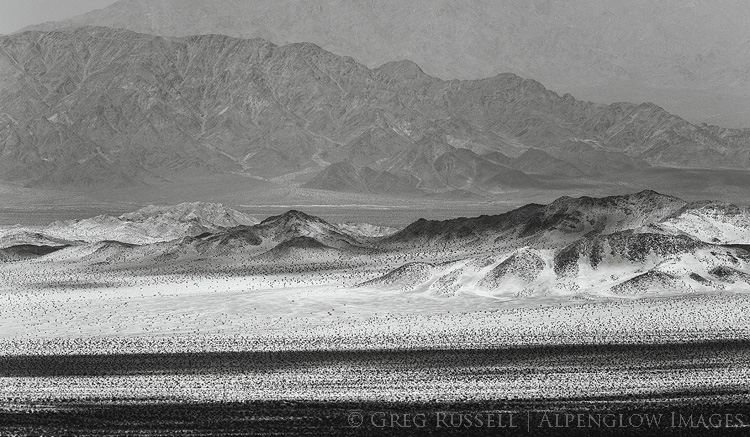

The health of the land is the standard by which we measure our work.

The popularity of photography as a hobby is at an all-time high. Combine this with the huge popularity of our national parks in general (see the most recent statistics on the top 10 most visited parks) and politically-fueled interest in our public lands; these all equate to increased impact on the land, with tangible effects.

We are responsible for the impacts on the landscape that result from our photography. In as much as we are bound to by realism in photography, we have the obligation to ask how things will be, how we want them to be, and how they should be. When we are unwilling to compromise the health of the land as our standard, advocacy will follow in our art. My unwillingness to compromise and my commitment to advocacy is the first point in my code of ethics.

Actions make advocacy tangible.

The idea of “commitment to advocacy” is a nice notion, but how can it be made tangible? Photographers might answer by saying that they hope their work inspires others to protect a particular wild or open space. Indeed, that would be wonderful (of course, publicizing locations carries its own caveats, which I discuss briefly later). What else? Print sales would be nice, especially if they can directly benefit a grassroots activist activity or environmental group somehow. Photographers could also consider donating image usage or prints to particularly worthy groups, many of whom are working on thin budgets as it is.

Finally, one that has me particularly intrigued is that photographers and backpackers don’t really “pay to play” in the same way that other outdoorsmen like hunters or anglers do; we aren’t taxed in the same way that hunters are for their ammunition, and we don’t purchase hunting or fishing licenses. This revenue is used to make habitat better for wildlife. We certainly reap the harvest from these habitat improvements, just as we enjoy well-maintained trails, and clean campsites, but what are we putting back into the coffers to make sure these things happen?

Until something more formal is put into place, the thought I have is to practice a self-imposed excise tax on goods that I buy for use in the outdoors. If I were to buy a new lens, or backpack, or headlamp, I would “tax” the purchase price, thus donating a predetermined amount at the end of the year to a group working on the ground to make the landscape better, and consequently making my experience better. If I’m not in the position to give financially, I would volunteer my time. Regardless of what we do as photographers, “advocacy” absolutely must be a tangible thing; this is my second point in my code of ethics.

“What counts finally in a work are not novel and interesting things, though these can be important, but the absolutely authentic. I think that there is a spirit of place, a presence asking to be expressed; and sometimes when we are lucky…and quiet in a way few of us want to be anymore, a voice enters our own…” – John Haines

Only by opposing the cultivation of disorder will we see a coherent body of work.

From a philosophical point of view, photography’s popularity is troublesome because–as the article above points out–we photograph everything but really don’t take the time to look at anything. Continuing on from the passage above from his book of critical essays Living Off the Country, John Haines writes, “I have come to feel that there is here in North America a hidden place obscured by what we have built upon it, and that whenever we penetrate the surface of the life around us that place and its spirit can be found.”

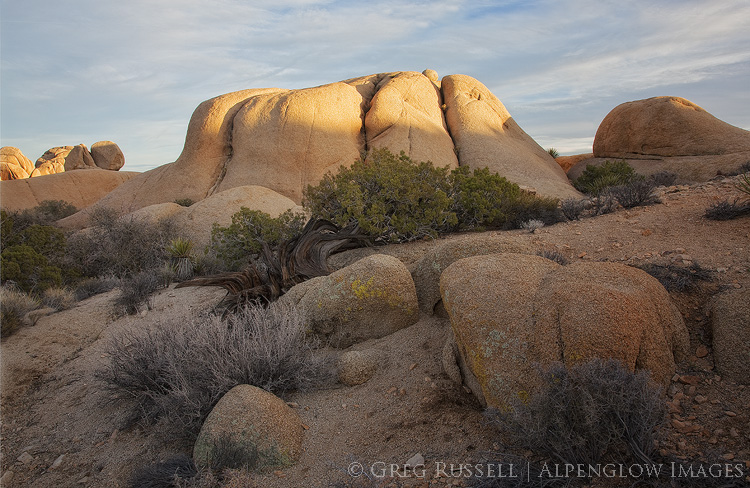

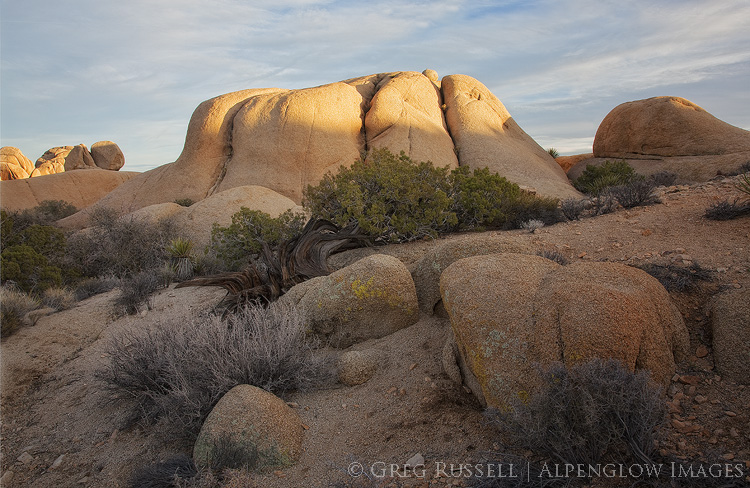

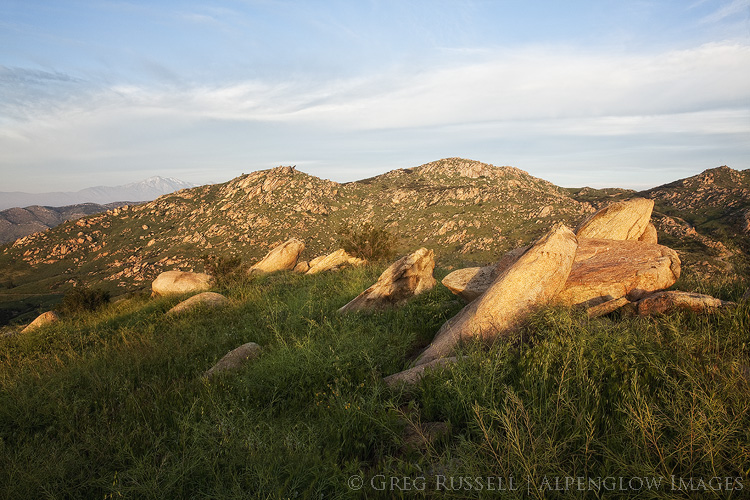

Perhaps now, more than ever, we need to know place. The third point in my code of ethics is to avoid passing photography fads and locations. Not only will I have become more connected with place by focusing on and producing a personal photography portfolio, it will reduce impact on places that are heavily photographed, thus improving the health of the land.

“There is no better high than discovery.” – E.O.Wilson

Ensure the experience remains sacred.

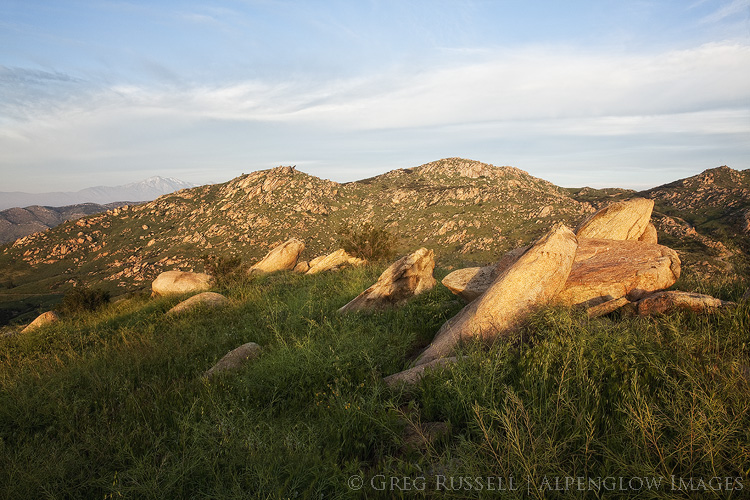

Photographers face a tough challenge. If we are truly advocates for the land, then we must inspire our viewers to want to protect it. However, at the same time, by inspiring them, visitation increases, ultimately creating greater impact. Reconciling these two things is no small task, and much attention has been given elsewhere as to the ethics of whether to reveal photography locations. Some photographers are unwilling to share anything about any of their “secret” locations. Others are more forthcoming, and yet others have developed apps that allow for “crowd sharing” of locations. It runs the gamut.

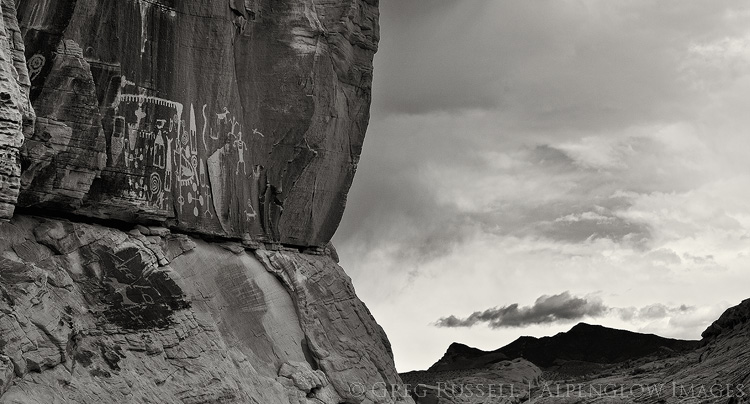

Personally, I lie somewhere between the former two points on the spectrum. I believe that it shouldn’t really matter where a photograph was taken–it’s all beautiful, and we should be stewards for it all. However, at the same time, I also believe that sometimes a general location is appropriate to include with commentary of a particular photograph. That said, I also believe that we need to find our own reasons to love anything (landscape or not), and that sentiment just doesn’t work if the reasons to love a place are dictated to us. So, the fourth point in my code of ethics is to share relevant information as appropriate, but I refuse to spoil anyone’s joy of discovery.

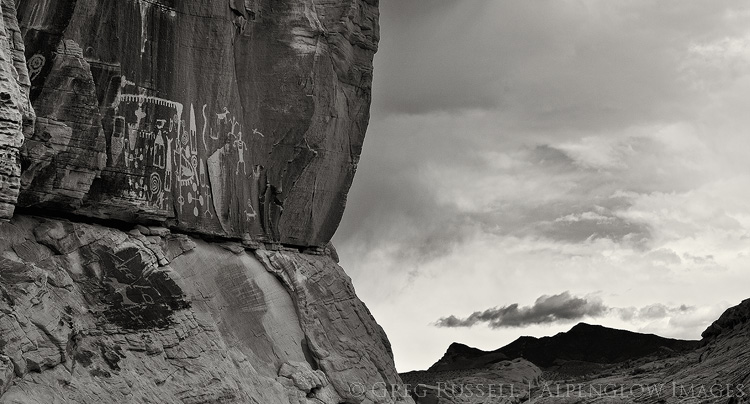

It’s worth mentioning archaeological sites here. There are some, which have common colloquial names and are visited regularly by hundreds of people. Their locations are practically common knowledge, and I will refer to them by their colloquial names from time to time. Others however, I will protect the location of, and will not give details for, except privately to trusted friends.

This is the beginning of my code of ethics. I’ll surely be adding things, but in the meantime what would you add? Many thanks to Samantha and Darwin for this thoughtful exercise.