“Laws change; people die; the land remains.” – Abraham Lincoln

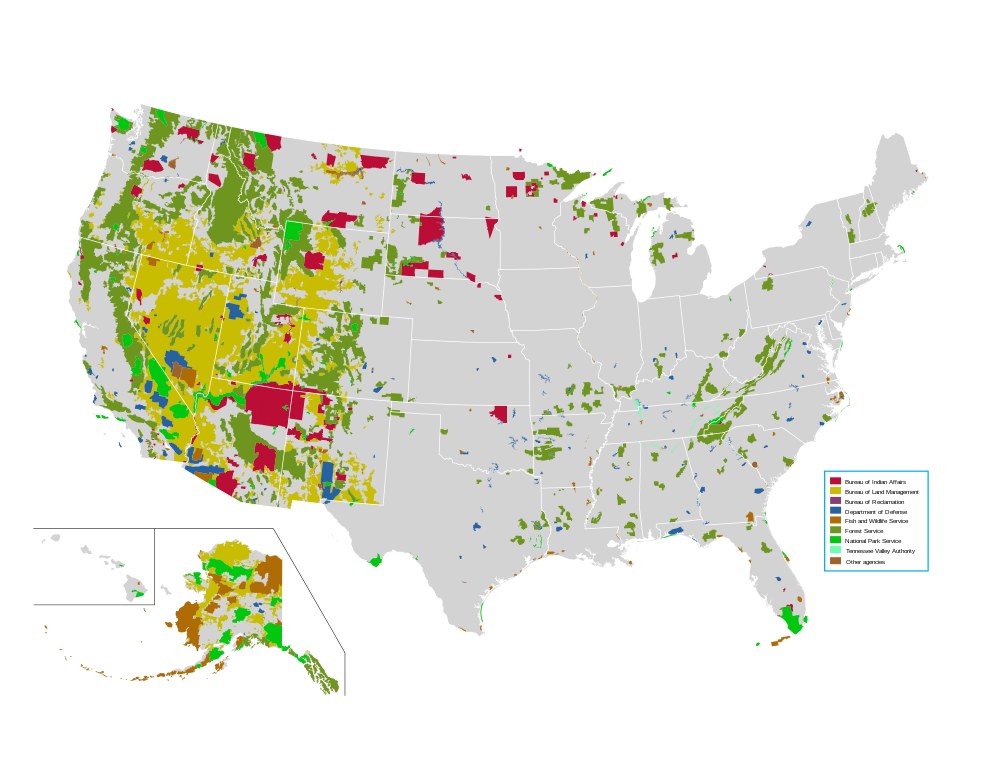

As a nation, we have made the decision to set aside large areas of land that remain largely free of development for the sake of saving them. This land comes in the form of national monuments, wilderness areas, national wildlife refuges, and of course our national parks, which have been called America’s best idea. In 2016, the National Park Service, which manages our national parks, celebrated its 100th anniversary. Indeed, each year, families, hikers, backpackers, photographers, and other tourists flock to our 59 national parks to see all that America has to offer, and it was truly a landmark year, worthy of grand celebration.

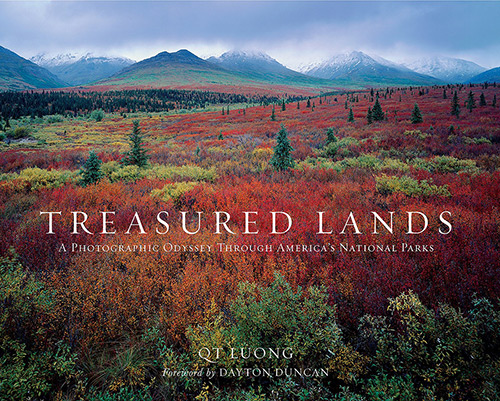

One of the most noteworthy things to appear in 2016 was QT (Tuan) Luong’s book, Treasured Lands: A Photographic Odyssey through America’s National Parks. Containing more than 500 photographs, 450 pages, and weighing in at 7 lbs, Treasured Lands is Tuan’s labor of love. Tuan is the only photographer to have made large-format images in every single national park, and the images in this book represent 20 years and hundreds of visits to all of them.

I first met Tuan on Photo.net discussion forums when I was just beginning taking photos, nearly 15 years ago. He weighed in on topics that varied from computers, to cameras, to photography locations. Then, as now, he has shown himself to be a master of the craft, the true consummate professional. So, when I read about the upcoming publication of his book, I knew it would be wonderful, and it is.

My first national park experience was at the Grand Canyon, backpacking with my Boy Scout troop. I was in junior high school, and we visited during spring break; it was snowing hard on the South Rim when we arrived. As many first-time backpackers and novice campers are, I was woefully underprepared and remember putting plastic grocery sacks over my socks in an attempt to keep them dry, among other things. Hiking into the canyon the next day felt incredibly treacherous on the ice that had formed overnight (in hindsight, it probably was), but cold and wet, I hiked on. However, I also remember the feeling of the sun at the river the next day; it warmed me and rejuvenated my soggy spirits. When we finished the trip, I couldn’t wait to get back to it…to backpacking, to the Grand Canyon, to as many national parks as I could visit. I was sold.

Since that Grand Canyon trip, I’ve backpacked the Grand Canyon several more times, and have spent countless hours in many of our other national parks. Yet, while the Park Service’s 100th anniversary is a landmark occasion worthy of celebration, it’s left me feeling a bit conflicted. Just before Christmas, I waited in line for nearly an hour to get into Joshua Tree National Park; in 15 years of visiting, I haven’t waited in line a single time. Zion National Park is considering a lottery system to determine who gets to visit the overcrowded canyon on any given day. Arches National Park has lines of cars reaching almost back into Moab from its entrance station several miles north of town.

Visitation to our parks is at a record high. Americans are visiting their parks. I can’t help but think that it leaves the Park Service in a bit of a conundrum on their 100th anniversary. They are tasked with preserving our national treasures, but at the same time ensuring access for the public, and those two tasks often don’t overlap. Park and Interior Department officials must be asking themselves, “at what point have we loved our parks to death, and how do we avoid it?” As a photographer who works in the national parks, how am I contributing to this? How are places–like Zion or Joshua Tree–that have traditionally been places of refuge for me going to change with this surge in visitation? None of these things is easy to reconcile, but Tuan’s book gives me hope, and a fresh perspective.

One piece of advice I would give to aspiring photographers is to look at as much photography as possible. Critique it, make lists of things you like and don’t like. Take notes on composition, lighting. This is the reason I became involved in the forums on which I met Tuan in the first place, but it’s sound advice, I think. However, this practice of critique can often be taken so far that photographers fail to let great photographs inspire them; Tuan’s images are indeed technically sound, but for someone who has had a quarter century love affair with our national parks, they serve the greater purpose of inspiration. Looking through Treasured Lands, I felt a deep happiness inside of me. These treasured lands will indeed remain for a long time, to be celebrated by generations to come. Thank you, Tuan, for that reminder.

Tuan has been a friend for a long time, but I have no financial interest in the success of Treasured Lands. It is simply a lovely book that you will enjoy for hours.